This is the second of a two-part post, synthesizing our final faculty seminar, with our final cohort of faculty fellows. These seminars have been at the heart of the TLH program, as we have aspired to cultivate agents of change in the classroom and beyond. During our 18 seminar sessions over the past two years, we’ve also tried to practice what we preach by fully engaging all participants in the co-learning and teaching process. One of the easiest ways to do this is by using an inventory method to make sure everyone is heard. It’s also an especially generative process for coming up with ideas that others can draw on in their teaching. For part one, check out Ideas for Teaching (and Teaching Outside) the Canon.

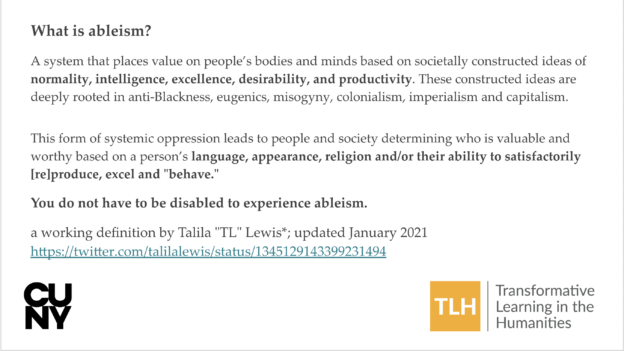

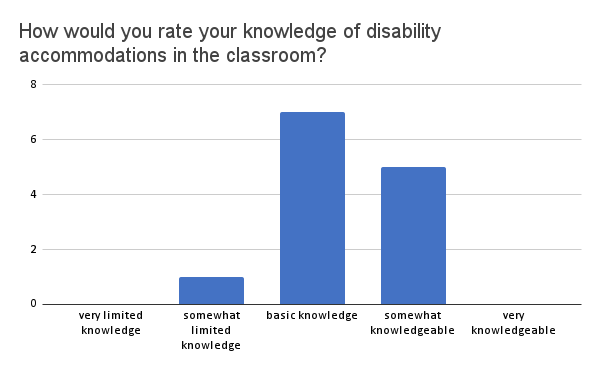

The second half of our seminar was dedicated to topics of care in the classroom. I spoke about disability and ableism, a pervasive force in our society, and especially in higher education. I also touched on the ways universal design can not only help students with disabilities, but has been proven to benefit all students. Accommodations for disabled students in higher ed are typically given when students show proof of a disability and make formal requests through an accessibility office. While the system is set up to make sure that their federal rights are guaranteed, it also inadvertently creates more work for disabled students. They may feel stigmatized by the process, or by a system that expects people to “game” the system.

Therefore, I invited our fellows to think about accessibility as care. Drawing on universal design principles, accommodations like having written materials in alternative formats for people who are blind or have low vision (i.e. someone who needs screen-readable text) also benefits the student who might want to read on a smart phone during their commute on the subway. It’s more common for students to request accommodations like extended time on assignments or exams, testing in alternative locations, or simply having breaks during exams. These types of requests can also benefit other students, by reducing anxiety associated with testing and grading, and by acknowledging and making time for universal needs. With that understanding, why not just make accommodations for all students? For anyone who might want to try it, I drew on Shelly Eversly’s idea for a care and community statement (below), which includes all of the resources Baruch students might need but not know about.

Accessibility Statement

We all learn differently and may need help or support in different forms. I do my best to make sure course materials are available in formats that can be printed or read on computer or smartphone before and after we meet as a class. I also strive to make sure our synchronous sessions are accessible. If anything about this course prevents you from learning or participating, please let me know. Your input makes sure I can develop a plan to make sure everyone succeeds. I also encourage you to visit the Accessibility Services Office to see if there are additional accommodations, tools, or supports you may not know about but could benefit from.

You might link to your campus accessibility office for additional support. Shelly also puts a version of this at the top of her syllabus each semester:

Statement of Care and Community

We care about you. We also know that you have a life outside of school, that everyone learns differently, and that you came to college to succeed. For all of these reasons and more, it is important for you to have ready access to the resources and services that are free and available to you as a student at Baruch. The college’s Student Services includes counseling services, services for veterans and for families, services for people with disabilities, and services for financial and housing emergencies. Healthy CUNY has food pantries accessible to all CUNY students in every borough. The college also offers free COVID testing.

As a Baruch student, you also have free access to Starr Career Development Center. The Writing Center offers one-on-one help with your writing. The Newman Library provides consultations on your research projects and online tutorials, as well as short term use of computers and other technology. You also have free access to study spaces and places to take your online classes.

In order to build and sustain our own community, let us collectively contribute to our shared class notes and resources. Everyone in this class is welcome to join our Whatsapp group for sharing information, course-related news, and positive vibes.

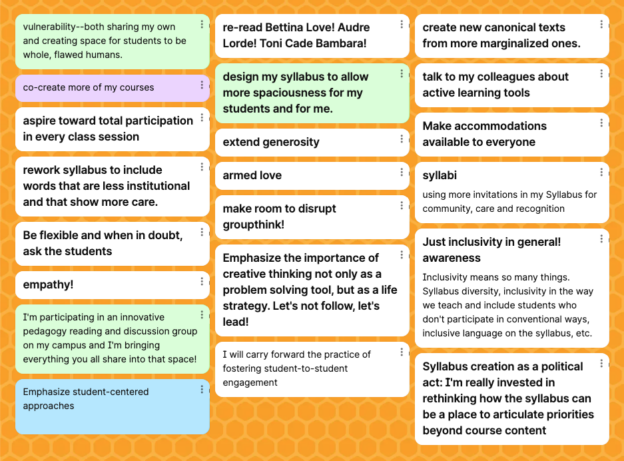

To close out our final session, we created a padlet and invited fellows to give us their final thoughts on taking what they learned from TLH forward with them. They gave us their thoughts anonymously and in the chat:

“vulnerability–both sharing my own and creating space for students to be whole, flawed humans.”

“re-read Bettina Love! Audre Lorde! Toni Cade Bambara!”

“create new canonical texts from more marginalized ones.”

“design my syllabus to allow more spaciousness for my students and for me.”

“talk to my colleagues about active learning tools”

“co-create more of my courses”

“aspire toward total participation in every class session”

“Make accommodations available to everyone”

“extend generosity”

“rework syllabus to include words that are less institutional and that show more care.”

“armed love”

“using more invitations in my Syllabus for community, care and recognition”

“make room to disrupt groupthink!”

“Be flexible and when in doubt, ask the students”

“Just inclusivity in general! awareness”

“Inclusivity means so many things. Syllabus diversity, inclusivity in the way we teach and include students who don’t participate in conventional ways, inclusive language on the syllabus, etc.”

“Emphasize the importance of creative thinking not only as a problem solving tool, but as a life strategy. Let’s not follow, let’s lead!”

“empathy!”

“I’m participating in an innovative pedagogy reading and discussion group on my campus and I’m bringing everything you all share into that space!”

“I will carry forward the practice of fostering student-to-student engagement”

“Syllabus creation as a political act: I’m really invested in rethinking how the syllabus can be a place to articulate priorities beyond course content”

“Emphasize student-centered approaches”

“I allow my students to miss two of our ten modules without penalty (nor excusing themselves) so that they can make a choice about when to prioritize other things”

“I hand out index cards at the beginning of class to let students pose a question to me that they don’t feel comfortable asking during class regarding lesson or coursework”

“This semester, I’m doing a lot of individual reflection on how we like to learn, where we like to read and/or write, and how we do our best thinking. We’re analyzing ourselves and sharing what we learn, what we already knew, and what surprises us. Just normalizing that has been super powerful for the class and for me!”

“I feel like there’s been a paradigm shift towards faculty being more in that quasi-counselor role – it would be great to have more training provided. Often doctoral students at the GC are not offered much training, if any, on how to teach, much less support mental health awareness in their classrooms.”

“And when I hear about personal difficulties (which I always emphasize they should only share with me if they want to), I give them as much flexibility as I can in my course, but also try to identify when and how I should refer them to counseling or other relevant CUNY services.”

Thank you to all of our amazing and caring faculty fellows!