The field of Library & Information Science is often downplayed within spaces of higher education. Librarians are frequently positioned as somehow different than “teaching faculty,” considered the real scholars and educators, with the Library at the margins. And in a way, it’s true that the cornerstone of information literacy instruction – commonly known as the ‘one-shot’ – is a challenge, different than a semester-long course immersion. Librarians are tasked with offering a single session within which students will do the following: Receive guidance on how to assess sources, identify a scholarly article, accord to the standards of academic writing, properly cite sources, and perhaps, hopefully, become energized by the zest of research. At least, this is what we aim for.

When we invited Shawn(ta) Smith-Cruz and Veronica Arellano Douglas for a Transformative Learning in the Humanities event hosted by the Mina Rees Library, all of this larger context was in mind. Knowing their work, the depth of their commitment as educators – we looked keenly forward to the interactive workshop, and to the potential insight and power in their vision(s) of transformative pedagogy.

We titled the event – Towards a Critical, Decolonized Pedagogy: An Interactive (Re)Visioning – to bring together the theoretical underpinnings of what is often termed “critical pedagogy,” in conversation with the more practical side of classroom experience. The goal, as stated in the event description, was to encourage participants to “reflect on specific examples of transformative learning praxis – moments when they sensed a shift in students’ understanding, and the associated context or framework that lead to that moment.”

As the event organizer, the practical emphasis was perhaps also driven by my own curiosity – so often these conversations are purely theoretical, and not fully grounded in a recognizable terrain. As a group, we discussed possible topics before the workshop. Questions came up, that would later be intertwined with the presentation themes: How do we know that a moment of transformative learning has taken place? Is it determined by an instinct, an observation, or something else? And to facilitate this possibility, what is the most important element in the critical classroom?

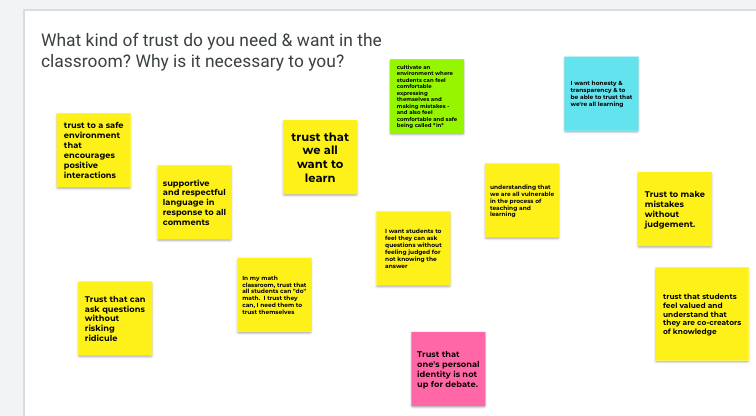

“What kind of trust do you need and want…and why is it necessary to you?” – Veronica Arellano Douglas

Interestingly, the event coalesced to center around the concept and experience of the presence of something distinctly less palpable, and not quantifiable by any assessment, rubric, or educational metric: Trust. Veronica Arellano Douglas expanded upon her own question above, stating: “As we explore power we need to explore trust – and understand that vulnerability isn’t the right answer to everything all of the time. Trust is a complex relational act and the more we talk about it and examine it, the better we will be able to cultivate that trust with people who learn with us.”

Douglas spoke of the lack of trust at times; the need to develop a genuine rapport with students, and the problem (so common to the single-session Library instruction session) of inheriting a classroom that may have its own dynamics, a set hierarchy of professor/student. She asked everyone in the room to contribute – either in the Zoom via chat, or a Google Jamboard (see below) – a response to a series of questions about trust in the classroom.

“There’s no way to get students through this portal without their being entangled, engaged…” – Shawn(ta) Smith-Cruz, on liminal spaces

In her presentation “A Critical Decolonized Pedagogy | A (re)visioning trifecta seeking Ancestral Connection,” Shawn(ta) Smith-Cruz addressed the process of learning, linking it to the idea of “liminal space,” as well as individual (or collective) ancestry. Using the ACRL Frameworks for Information Literacy as a starting point, Smith-Cruz expanded upon what elements are necessary for learning, offering Laura Rendón’s “Sentipensante Pedagogy” as a parallel vision of the traditional classroom space. Identifying some of the unspoken assumptions of academic culture, such as “Agreement of Separation – that teaching and learning are linear,” and that the student studies the subject matter from a distance,” Rendón offers an alternative, involving “the balance between inner and outer knowing,” as well as “respect for diverse cultures” as a primary cornerstone for all educational ventures.

Alongside a series of compelling images, Smith-Cruz identified “liminal space” as a kind of rite of passage, even a portal: “It’s the feeling of discomfort, the moment of receiving of new knowledge, for which learning is possible…the experience of troublesomeness, of worrisomeness, unsettling, disturbing, stuck-ness – and whether we want to get students to that place.” This is a refreshing departure from not only the student as passive learner, but also the expectation -and often the unspoken goal – of a static, neutral, and conflict-free classroom environment.

I asked Smith-Cruz if the liminal space was also an ephemeral space – something temporary, that we enter into and then exit, thereafter changed. She responded: “The Oxford English Dictionary defines ephemeral as transitory, i.e. for a short time. With that I’d say, it requires a very present experience, embodied, and can be identified as a passageway, portal, so yes, it would be ephemeral, but it is lasting, and ever-impacting – as if a coloring with permanence, and so, forever imprinted.”

For Smith-Cruz, there are clearly intersections between the various forms of knowledge that we each bring to the traditional classroom environment, and the radical potential within. Just last year (2020), Smith-Cruz was awarded the ACRL Women Gender & Sexuality Studies Award for Significant Achievement, sponsored by Duke University Press, for her work archiving and exhibiting the Salsa Soul Sisters, the first lesbian of color organization in the United States. To facilitate an archival collection of this kind – exhibited at the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts, Brooklyn College, and The New-York Historical Society – requires a unique level of trust, and community-based commitment. Through both her archival work, and the invocation of liminal spaces, Smith-Cruz offers a powerful model for teaching and learning – based on a belief in people that is itself transformative, and deep.

“The possibilities that exist between two people, or between a group of people, are a kind of alchemy.” Adrienne Rich, On Lies, Secrets, and Silence

The experience of this workshop – both from the audience feedback and presentations by Smith-Cruz and Douglas – brought to mind a favorite quote by the poet Adrienne Rich (above). In her 1975 essay “Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying,” Rich speculated – “I fling unconscious tendrils of belief, like slender green threads, across statements such as these.” Emphasizing the importance of trust, and belief in the words of others, towards hope – she also writes that a revelation of truth “may bring acute pain, but it can also flood me with a cold, sea-sharp wash of relief.”

To focus on trust is itself a much-needed provocation, a radical axis on which to define the critical classroom. A question mark, in a sense, hovers around and within our interactions. Do we trust each other, by default? How can trust be built and then maintained? Whose words are considered trustworthy – whose conclusions, valid? Teaching information literacy is surprisingly close to this fertile edge of belief, of trust, of Rich’s “sea-sharp wash of relief.” We must, in a sense, welcome the stranger – be willing to ask the questions that challenge our primary sense of being, of what we know.How do we begin to open our minds and hearts, to layers of knowing that may make us uncomfortable?

Unpacking these questions can be a part of the invitation to learning, and we are honored to have been able to partake in this process alongside Veronica Arellano Douglas and Shawn(ta) Smith-Cruz. To engage in a collective reflection process also points towards the potential of decoloniality: towards expansive (re)visions of the future, and what we can therefore know.

Shawn(ta) Smith-Cruz is an archivist at the Lesbian Herstory Archives, an Assistant Curator and Associate Dean for Teaching, Learning, and Engagement at New York University Division of Libraries. She is a Co-Chair for the board of CLAGS: The Center for LGBTQ Studies at the Graduate Center. Shawn has a BS in Queer Women’s Studies from the CUNY Baccalaureate Program, an MFA in Creative Writing/Fiction, and an MLS with a focus on Archiving and Records Management from Queens College. She is the 2020 recipient of the ACRL Women Gender & Sexuality Studies Award for Significant Achievement, sponsored by Duke University Press for her work archiving and exhibiting the Salsa Soul Sisters, the first lesbian of color organization in the country.

Veronica Arellano Douglas is the Instruction Coordinator at the University of Houston Libraries. She received her MLS from the University of North Texas and BA in English from Rice University. Veronica writes about teaching, critical information literacy, and intersections of librarianship, gender, race, and ethnicity. She blogs at veronicaarellanodouglas.com and acrlog.org and is the co-editor of the recently published Library Juice Press book, Deconstructing Service in Libraries: Intersections of Identities and Expectations.

Elvis Bakaitis is currently the Interim Head of Reference at The Graduate Center’s Mina Rees Library. Bakaitis is proud to serve on the University LGBTQ Council; the board of CLAGS: The Center for LGBTQ Studies; and LACUNY Diversity & Multicultural Roundtable, and holds an MLIS from Queens College and Certificate in Geriatric Care Management from the Brookdale Center for Healthy Aging at Hunter College.