by Ria Banerjee, Sarah Hoiland, and María Julia Rossi

As educators, we are typically impelled to produce content–course plans, public lectures, writing and speaking in various registers is central to what we routinely do. It is rarer for us to get opportunities to “fill the well,” so to speak, and a TLH grant provided us a forum to develop our understanding of contemporary fiction that is outside our disciplinary subfields but aligns with our interests. After discussion among a core group of five planning faculty (Julia, Ria, and Sarah are the names on record for this group of CUNY friends), we decided on some ideal parameters for our planned event: we wanted to read recent novels by women of color, intentionally working against the Anglophone publishing industry’s bias, and we chose works focused on the US with an eye on global interconnectivity. We wanted to attract participants from a range of work and professional experiences, as having only educators might narrow our conversation. Finally, we wanted to give space to student voices in designing and leading our discussions, again to foster a broad conversation that would not be possible at, say, a disciplinary conference. We settled on three particularly timely novels.

In distinct ways, Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing (2016), Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive (2019), and Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age (2019) speak to the stresses and challenges of US citizenship in transatlantic, continental, and transcultural terms. They are carefully crafted novels, widely recognized for their literary qualities. And, they are social novels as well as philosophical and historical ones. We agreed that it would be useful to read these novels carefully, as some of us intend to incorporate them into the courses we teach in future. But even more importantly, all three novels looked fun, intellectually and emotionally stimulating in a pandemic semester when most of our colleagues, students, and friends are working under very strained conditions.

The primacy of storytelling in both Homegoing and Lost Children Archive weaves history into contemporary journeys of what it means for characters to return home and what even constitutes our ideas of “home”. Our third meeting will take place at the end of May, but the first two novels’ shared interest in historical contexts and their desire to archive public and personal recollections allowed our reading and discussion group to make connections across these very different texts. Both authored by young women of color, the novels pushed us to consider the authors as allies or fellow travelers with deeply personal connections of their own to the subjects raised in their writing: the transatlantic slave trade in Gyasi’s writing and the migrant crisis at the US southern border in Luiselli’s.

In Homegoing, Gyasi materializes intergenerational trauma through two necklaces that are passed down from mother to daughter, one that remains in the family and another that is lost when a young woman is sold into slavery. In Lost Children Archive, Luiselli creates fictional archives that are literally and symbolically unpacked on a family’s cross-country journey to record the echoes of our past and to retrace migrant children who are lost. By tracking the development of narrative objects as symbols, and of shared textual tropes like motherhood and the inheritance of intergenerational trauma, our reading group has come to understand each work as a stop on a longer textual journey that we are taking together.

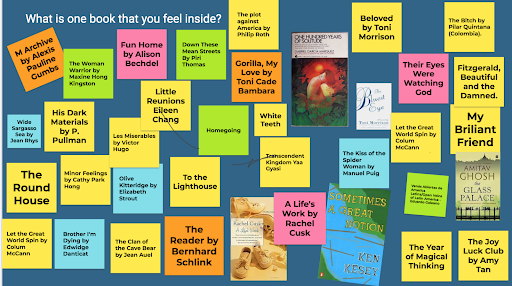

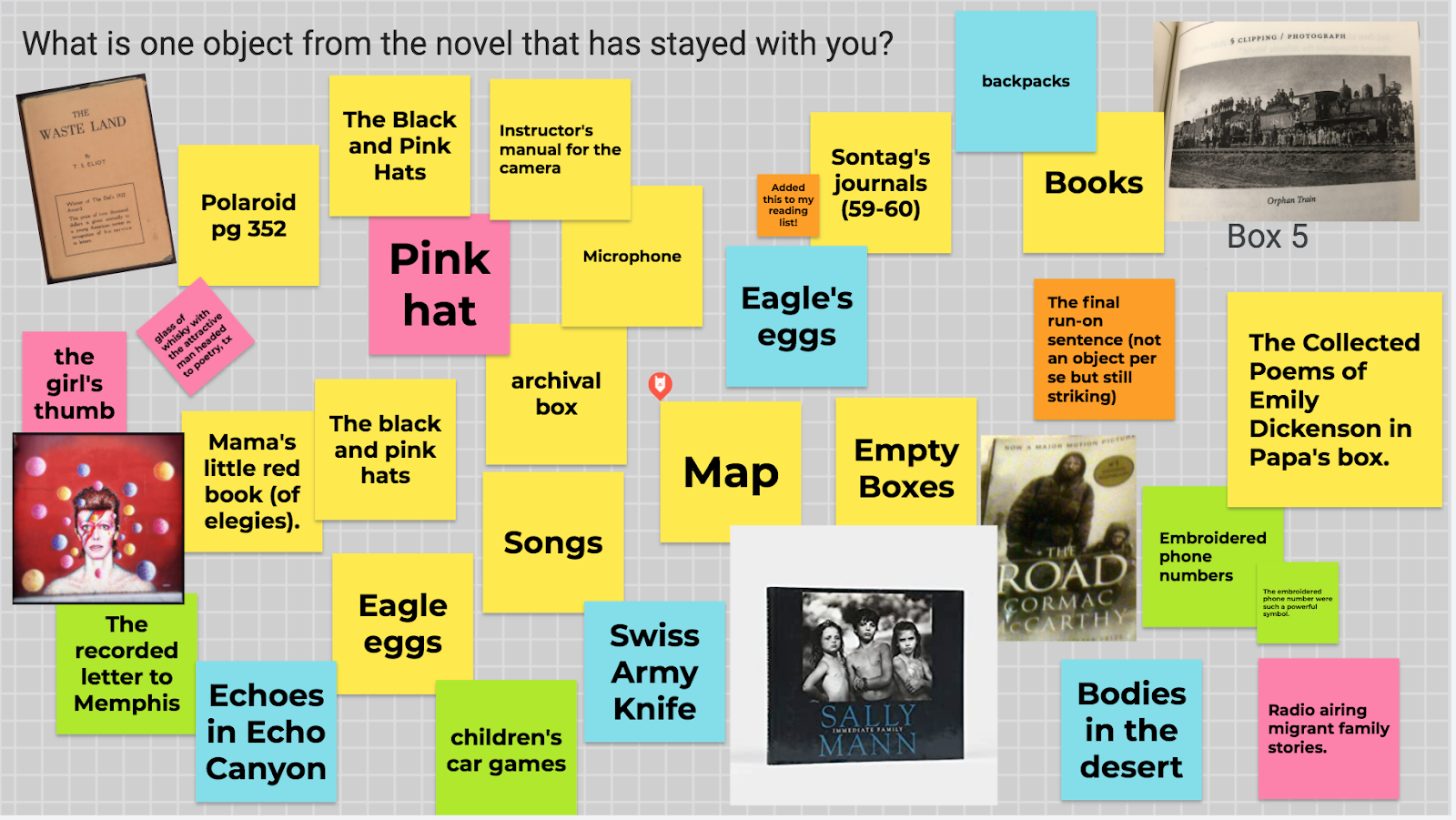

In addition to one faculty leader for each session, Hostos and Kingsborough Community College alumna (subsequently at Hunter, Baruch, Brooklyn and the GC), have served as co-facilitators for each session. Isatou Batchilly, Denise Herrera, and Jozette Belmont have had deeply personal reactions to the novels, and offered complementary discussions of identity politics that restored a certain immediacy to our sessions. We did not intend to have purely academic discussions, and our co-discussants add their perspectives as political campaigners and social workers whose professional lives intersect with textual content. Through interactive icebreaker activities drawn from questions raised by the novels, the 40 participants in Women Rewrite America were asked to co-create a digital archive of our experience of reading together. These introductory activities proved to be effective for a large group of strangers coming from all over the US and a variety of academic and nonacademic roles, united only by an interest in the reading material. For faculty participants, this translates into an activity that can be easily adapted for the classroom. TLH made it possible for us to invite one of the authors, Valeria Luiselli, to attend a session, adding fresh depth to her personal and political involvement with issues that are important in our own intellectual and work lives.

It is difficult to provide culminating thoughts on our experience because, well, the series ends at the end of this month. But aside from logistical reasons, coming to a quick summative response is contrary to our purpose when planning this 3-part, 3-month event. In the past few years, there have been several strong arguments put forward by philosophers, psychologists, and economists embracing slow thinking or “doing nothing.” Vincenzo Di Nicola compares Slow Thought to the Slow Food movement, arguing that slow thinking “is preservative rather than conservative,” and “founds a kind of contemporary commune” in which participants might respond to their own time and place while also “spreading organically as communities assert their particular needs for belonging and continuity against the onslaught of faceless government bureaucracy and multinational interests.” Writing more recently from the middle of the pandemic, Apoorva Tadepalli asks us to resist the urge to always be doing something. Do nothing, she urges; consider the pandemic “an opportunity not to ‘get your life back on track,’… but to experiment with nothingness, with a failure of productivity.”

Breaking away from the relentlessly positive self-help rhetoric that saturates US popular media (and also perhaps US academia!), Tadepalli recommends that we “do nothing” except take time to try and find our own humanity, “tell and listen to stories.” This is no easy task in itself, as many who are working from home will attest. Still, both Di Nicola and Tadepalli speak to a tacit purpose behind our reading and discussion series to create time and space to just read and interact. What the fruits of such an exercise will be remains, happily, to be determined.

Ria Banerjee is an Associate Professor of English at Guttman Community College.

Sarah Hoiland is an Associate Professor of Sociology at Hostos Community College.

María Julia Rossi is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Modern Languages at John Jay College.