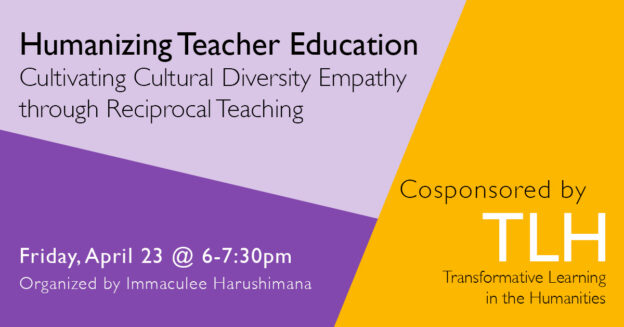

This post was written by Contributing Author Professor Immaculée Harushimana (Lehman College), who recently organized a TLH-sponsored event, “Humanizing Teacher Education: Cultivating Cultural Diversity Empathy through Reciprocal Teaching.”

As a result of European occupation, formerly colonized nations have been introduced a colonial curriculum which, naturally, executes the Eurocentric education agenda. Throughout my educational system, I was never aware that I was being indoctrinated. I loved learning and I loved getting good grades because my parents believed that it was only through education that I was going to escape poverty and also pull them out of it. To some extent, they were right. Education opened to me the door to academic and economic success. Along with that advantage, however, it also transformed me into an instrument of the colonial agenda. In this brief article, I am offering a reflection on my transformational journey from being a blind status-quo English educator to a transforming, critical literacy advocate.

Majoring in English as a Foreign Language Implies Embracing the Status-Quo Curriculum

In ex-colonial nations, teaching takes place in an ex-colonial language, and the curriculum followed as well as teaching materials have been written by western authors who promoted western thinking. As an English teacher, I had no choice but to promote the language and the culture of England and the standards of the English language. Based in the African context, without any direct contact with native English-speaking societies, I was naively thinking that I was helping Burundian children to escape poverty. In the meantime, they were being taught to follow the standards of the English language, to read about and appreciate English authors and to write about them. Then, in 1993, I had the opportunity to travel to the United States of America to pursue graduate studies in the same field. That is when my eyes started to open slowly, and I noticed the depth of indoctrination I was being subject to. Not only was I learning a subject that was someone else’s, I was learning someone else’s culture and ideologies while, through imperfect A’s, I was constantly reminded that I could not produce native speaker quality of work. In other words, my work would always be “less than”. I would learn more about that concept during my doctoral program, when I was exposed to the literacy issues of minority children in US schools. During the Ph. D. journey, I was also introduced to different, competing rhetorical traditions, including the current-traditional, the expressivist, the social-constructivist, and the process-centered approaches (Berlin, 1982). All these theories seemed to be based on the assumption that all college entrants had had a similar educational experience. That is when I started to realize that something was wrong, but exactly what? I could not tell.

Experiencing Linguicism as an Eye Opener

After obtaining my Ph. D., i.e., in 1999, I was majorly hired part time to teach college composition at different institutions in high diversity areas of New York City. Later, when I had a tenure track position, I was assigned to teach a language and literacy course to in-service and pre-service teachers. I was excited by those positions, for I had been confidently thinking that I was qualified to teach English language and composition topics with assurance. Everything changed when I experienced rejection from the students who claimed that I was not qualified to teach them, and program coordinators who seemed to believe them and would not allow me to teach major courses that I had worked hard to master. I found myself always teaching the only one course that colleagues hated to teach and that my students hated to learn—language and literacies in secondary classrooms. For several years, I built the course around topics on academic language and literacy, digital literacies, and new literacies. Such was the teacher certification mandate from New York State Department of Education. Due to the repulsive attitude mainly of white students, I stayed away from critical pedagogy/critical literacy matters, even if had been exposed to Paulo Freire’s ideas of the pedagogy of the oppressed (1970) since I arrived in the United States, back in 1993. Ironically, encounters of linguicism, with good doses of racism and Afrophobia, invigorated my mission to ensure that my seemingly struggling students of color achieved the ability to understand academic texts and write essays in proper academic English. I was the typical puppet of the hegemony, for I could not call myself a hegemonic intellectual (Giroux, Freire & McLaren, 2011). Alas, my good intentions were not appreciated.

The Awareness

Based on my own experience with rejection and my own children’s ordeal to adapt to the secondary school (English) curriculum, I began to develop my scholarship in the area of African immigrant children’s school adaptation (Harushimana, 2013). As I was gathering the literature for my research, I found out about critical theorists, especially Jonathan Kozol and Ira Shor, and my awareness of minority children’s challenges with academic discourse increased. One thing led to another, and I decided to add to my course a section on critical pedagogies where I had the class read and respond to works that denounced the savage inequalities of the United States k-12 school system (Kozol, 2005; 2012). In the process, I found some room for my own work on African-immigrant children (Harushimana, 2013) as well as well works by other scholars who explored issues of unequal educational opportunities for African American children (Delpit, 1995) and other immigrant children (Ahmad & Szpara, 2003; Endo & Rong, 2011; Lukes, 2014).

The Transformation

At first, I was the leader of the discussions on the section on critical (race) pedagogies, but I very quickly realized that I was too passionate, biased and angry. My students, especially white teaching fellows, felt uncomfortable and complained that they had not come to learn about African American or African immigrant children. They wanted to learn how to teach Shakespeare and other canonical works of literature to the predominantly black and brown Bronx children. I felt a bit frustrated but not deterred. After a deep reflection, I came up with a new teaching strategy. Instead of me guiding the discussions, I decided to require that students give presentations on articles that I had curated on critical (race) pedagogies while I played the moderator-discussant role. To my greatest relief, the strategy resonated with many students, especially from among non-teaching fellows. I received very positive feedback and compliments for opening my students’ eyes to the challenges of being a minority child or an immigrant child of color in the United States School system. Through their career choice narratives, some students have showed empathy towards the miseducated minority and immigrant-descent children of color and vowed to be part of change. It gives me hope when I read a statement from a future teacher that reads,

I care about giving back to the people that welcomed me with open arms as a sad, lonely, rejected child, that I’ve seen treated unjustly time and again. [. . .] I plan to spend my life serving low-income communities and making education more equitable in the United States. (Orlin, written communication, 2021)

Finally, not all white, privileged teacher candidates view their teaching mission as being to save poor, underprivileged children from themselves.

Immaculée Harushimana is a 2018-2019 Fulbright Scholar (Mzuzu University, Mw) and Associate Professor of TESOL and English education at Lehman College, City University of New York. Her major area of inquiry is in critical linguistics and its implications for literacy instruction to adolescents in a globalized world. The underlying theme of her research is linguicism as reflected through African-born immigrants’ academic and professional integration; multilingual identities; and alternative discourses.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, I., & Szpara, M. Y. (2003). Muslim children in urban America: The New York city schools experience. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 23(2), 295-301.

Berlin, J. A. (1982). Contemporary composition: The major pedagogical theories. College English, 44(8), 765-777.

Delpit, L. (1986). Skills and other dilemmas of a progressive black educator. Harvard Educational Review, 56(4), 379-386.

Endo, R., & Rong, X. L. (Eds.). (2011). Asian American education: Identities, racial Issues, and languages. IAP

Freire, P. (2018). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Bloomsbury publishing USA.

Giroux, H. A., Freire, P., & McLaren, P. (1988). Teachers as intellectuals: Toward a critical pedagogy of learning. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Harushimana, I. (2013). Foreign-born minorities and American schooling: The African- born adolescent’s plea. In I. Harushimana, C. Ikpeze, & S. Mthethwa-Sommers (Eds.), pp. 140-155. New York: Peter Lang

Kozol, J., 2005. The shame of the nation: The restoration of apartheid schooling in America. Crown.

Kozol, J., 2012. Savage inequalities: Children in America’s schools. Crown

Lukes, M. (2014). Pushouts, shutouts, and holdouts: Educational experiences of Latino immigrant young adults in New York City. Urban Education, 49(7), 806-834.

I truly appreciated your insights and reflections on the road you traveled through being “woke” to being a purveyor of practices to awaken. Thank you.