This post was written by Contributing Author Matt Brim. Matt Brim is Professor of Queer Studies in the English department at College of Staten Island, with a faculty appointment at the Graduate Center in the Women’s and Gender Studies M.A. Program.

Part 1: The Plan

On February 24, 2021, I facilitated a workshop as part of the Transformative Learning in the Humanities series, an initiative of a larger TLH grant at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. The workshop was titled “Teaching Black Queer Studies as General Education for the Public Good.” I had several goals in mind for the session:

1. To frame Black queer studies—and Black queer literary inquiry, specifically—as a site of rich literacy practices that teach us to read for, toward, and in the service of Black queer experience and world-making through language. I am guided here by poet and scholar Tracie Morris, who writes

[Black people] know fantastic world-making through words when we see them. We always make new worlds. We refashion them out of the sounds we said at the beginning of humankind. We make them out of all the atoms of sounds even those spoken to harm us. This is what we do: Out of all these building blocks we wail a world, create joyful noises, the first thing and new things with words.1

2. To suggest that, in the main, we have all been denied Black queer literatures and literacies in formal schooling contexts. The result, as intended, is that we have been taught to read almost exclusively in ways that depend narratologically on the entwined underlying storytelling principles of anti-Blackness and anti-queerness. Our miseducation has produced, I wanted to suggest, a general state of Black queer illiteracy. Because we have not been taught what we should have been taught—to read Black queer literature—readers must now, to quote James Baldwin and the Black Pentecostal tradition, “do our first works” of knowing the world through story all over again.2 Black queer studies is, in this sense, a site of much-needed remedial reading education.

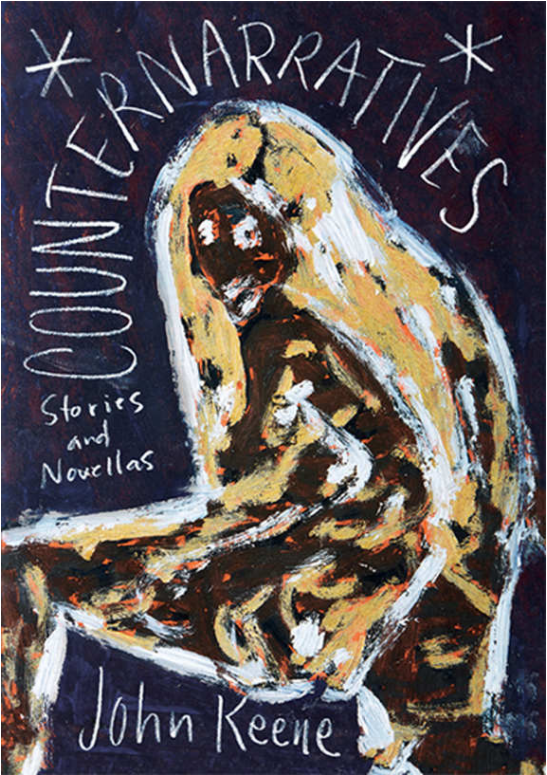

3. Another primary objective was to introduce workshop attendees to a text for teaching and learning Black queer literacies, John Keene’s 2015 collection of short stories and novellas, Counternarratives.3

4. Finally, the session aimed to make one broader pedagogical point: that the exemplary worksite for learning to “counterread” with and through Black queer literature is the general education classroom/curriculum within public higher education institutions. Here, I extract Black queer studies from specialized, advanced, upper-level undergraduate and graduate educational contexts and, more emphatically, from selective and exclusive classrooms and colleges. I defined the public good of learning Black queer literacies as that which can be good only if it is good for students like my CUNY students and their communities. Public, accessible higher education institutions, including community colleges, are the sites from which the general work of rereading for Black queerness can best be accomplished, if for no other reason that that is where most college students are.

Part 2: The Feelings

In retrospect, I had a feeling the session wasn’t going to go well. Why? I knew the material, I had a lesson plan typed up and highlighted, I felt competent on Zoom after nearly a year. More importantly, I had pedagogical experience to rely on: I had previously taught the text we’d be discussing in the workshop several times in undergraduate and graduate courses at the College of Staten Island. But a question or an insecurity remained, unlinking preparation from a predictable outcome.

I knew that reading an entire short story (Keene’s opening story, “Mannahatta”) together on Zoom would require about ten minutes of intense focus. Would it be too much? I pushed that question out of my mind—this is such an amazing story, the time commitment will be worth it, I told myself (and, frankly, I still have trouble letting go of that perspective).

I also knew that organizing attendees’ responses to the story around *not knowing* could be confusing and could put participants off-balance. The “not knowing” questions that I designed were meant both to establish a sense of illiteracy/readerly inexperience and to give this group of readers a way to enter and unlearn those illiteracies: “What don’t we know or what don’t we recognize when we read this story?” “Why don’t we know it and how can we better frame our not knowing (illiteracies)?” “Where and how can we best learn about our unlearnedness when faced with this Black queer text?”

To work through the disorientations created by the above questions, I planned to draw on CUNY colleagues’ scholarship as a way of orienting the group more comfortably amidst potentially uncomfortable questions. I had film scholar Racquel Gates’ recent New York Times piece “The Problem with ‘Anti-Racist’ Movie Lists” in mind. Gates writes, “During this reflection on blackness and media, we must focus on the complexity and brilliance of Black film on its own merits. Now more than ever, we should return to Black narratives that decenter whiteness or ignore it altogether, films that connect audiences with the pathos, joy and even treachery of the Black characters and lives they depict, the films that recognize their complex humanity.”4 I love quoting from the work of CUNY faculty and students, and I have seen that teaching move make a class cohere around a sense of pride for one of our own.

Part 3: The Outcome

As the session went along, the attendees (many of them my CUNY colleagues), were as generous and helpful as they could be. They did the work I had planned for us by reading the text, making astute comments, and volunteering to help me navigate the chat as I multitasked in the virtual space. Several wrote to me afterward that they had enjoyed and gotten something out of the workshop.

Yet as teachers, we know the feeling when a planned lesson doesn’t “land.” We can feel it. For instance, I didn’t leave enough time to integrate Gates’s quote into the discussion, and that’s very disappointing. What interests me right now, though, is the relationship between my post-workshop feeling of not landing and my pre-workshop feeling that the session might not land. What is the connection between that tickle of doubt on the front end of the workshop and the unsatisfying itch that remains unscratchable after a teaching failure on the back end? Does the tickle predict the scratch? Can we identify or bring to consciousness our doubtful pedagogical feelings as a way of resetting, rethinking, and revising our planned work, all in the hopes of avoiding the latter feeeling?

I don’t have an answer, but I realize it’s a question that has lived in my teacherly brain for years. Interestingly, not until my Zoom workshop have I been able to formulate it as such. Is there a lesson here that virtual educational spaces can teach us, a lesson that we can hold on to even once we return to in-person teaching? How else might we understand the connection between these two pedagogy feelings? Do they have anything to do–and here we see the real stakes of the question–with teaching Black queer studies and other fugitive literacies, ones that we’ve been educated against? It’s a question I hope to think further about going forward.

[1] Morris, Tracie. Who Do with Words: (A Blerd Love Tone Manifesto). Victoria, TX: Chax Press, 2018.

[2] Baldwin, James. The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948-1985. New York: St. Martin’s, 1985.

[3] Keene, John. Counternarratives. New York: New Directions, 2015.

[4] Gates, Racquel. “The Problem with ‘Anti-Racist’ Movie Lists.” New York Times, July 17, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/17/opinion/sunday/black-film-movies-racism.html

Matt Brim is Professor of Queer Studies in the English department at College of Staten Island, with a faculty appointment at the Graduate Center in the Women’s and Gender Studies M.A. Program. He teaches a variety of courses in LGBTQ literature and women’s studies, often with a focus on black feminist/queer studies. His most recent book, Poor Queer Studies: Confronting Elitism in the University (Duke University Press, 2020), reorients the field of queer studies away from elite institutions of higher education and toward working-class schools, students, theories, and pedagogies.